Not so hard to believe

by Tom Sullivan

It's hard to believe. Not two weeks ago, Labor Secretary Alexander Acosta announced his department would induct former President Ronald Reagan into his department's Hall of Honor, joining Mother Jones, Eugene Debs, and Cesar Chavez.

We pause while you recover from blowing coffee out your noses.

Acosta cited Reagan's leadership of the Screen Actors Guild beginning in 1947. There was no mention in the press release of Reagan's destroying the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) when in 1981 he fired its 11,000 members and imposed a lifetime ban on rehiring the strikers.

AFSCME (the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees) responded:

This is no small insult to working people. It’s a slap in the face to all those people whom the Hall of Honor is supposed to honor. Its mission is to honor people “whose distinctive contributions in the field of labor have elevated working conditions, wages, and overall quality of life of America's working families.”The Trump administration just elevated a union buster to the Labor Hall of Fame. Maybe it's not so hard to believe.

That applies to a very special group of people who put workers’ rights – and the struggle for dignity on the job – ahead of all else.

During the course of his presidency, Ronald Reagan became the most powerful union buster in the world. He stacked the National Labor Relations Board with officials who vehemently opposed unions, causing long-term damage to collective bargaining and workers’ rights in the United States.Union membership in the workforce has dropped in this country since the from middle 1970s from 26.7 percent 13.1 percent. Reagan's actions accelerated that decline and contributed to wage stagnation for the bottom 70 percent of American workers since his tenure.

After the air traffic controller debacle, corporations became emboldened and targeted unions with a new zeal, illegally firing workers for organizing with the knowledge that they could largely evade punishment under Reagan’s labor board.

A few simple but bold legal reforms would make a world of difference. First, Congress could pass laws to promote multi-employer bargaining, or even bargaining among all companies in an industry. If all hotel brands, all fast-food brands, all grocers or all local delivery companies bargained together, none would be placed at a competitive disadvantage as a result of unionization, which is often the main reason employers resist it so fiercely. Second, Congress could ensure that organized workers can bargain with the companies that actually profit from their work by expanding the legal definition of employment to cover more categories of workers.We live in a period, Shaun Richman writes at In These Times, when "'corporate persons' have established free speech rights [and] a union—a collection of actual persons—has no similarly recognized protections." The 14th Amendment, in essence, has yet to ensure labor and management enjoy equal treatment under law.

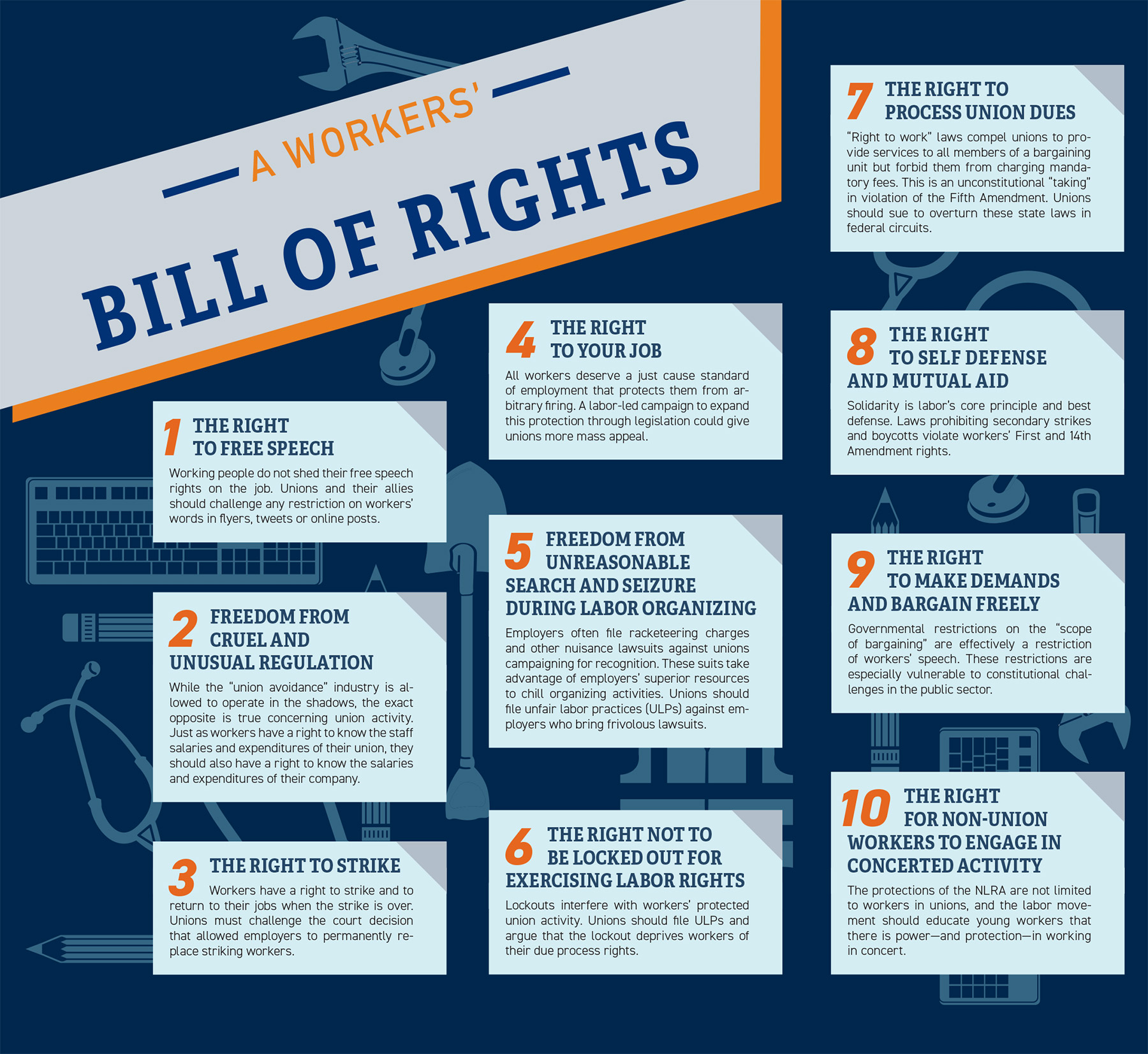

Unions must reverse a half-century-long strategy of avoiding the courts and mount legal and political challenges to labor laws that infringe on workers’ speech, curtail their bargaining power and deny them the right to extend solidarity to fellow workers. This is a long-term strategy, one made longer-term by the inability to appoint progressive federal judges in the near future. But if we are ever to restore key protections for labor, we need to demand a workers’ bill of rights.He happens to have one to propose (above).

In a 2009 study, Cornell University’s Kate Bronfenbrenner found that employers utilized these captive audience meetings in nine out of 10 union elections. Employers threatened to cut wages and benefits in 47 percent of documented cases, and to go out of business entirely in 57 percent of cases. In one in 10 instances, bosses actually hired goons to impersonate federal agents and lie about the process. Not surprisingly, unions lose 57 percent of elections when employers run these “captive audience” meetings.Hard to believe again.

Ironically, corporations have argued for—and won—the right to hold these meetings on the grounds of their First Amendment rights as “persons.” Yet union advocates possess no equivalent right to hold their own “vote yes” meetings.

Labor groups might start by challenging the excessive restrictions on signal picketing (efforts to embarrass unfair employers without an explicit call for a boycott). Noxious hate groups such as the Ku Klux Klan and the Westboro Baptist Church have seen their pickets vigorously defended by the courts. Unions should argue that to restrict signal picketing is to violate workers’ First and 14th Amendment rights.Anyone who lived through the aftermath of the 2008 financial meltdown, bailouts, and non-prosecutions of Wall Street bankers knows it, feels it down deep in their guts that business interests have tipped the law, the economy, and the power in this country in their favor. If we as a nation are unable to roll back corporate personhood in the courts and restore democracy that way, unions should at least enjoy equal status as the beginning of a counterbalance.